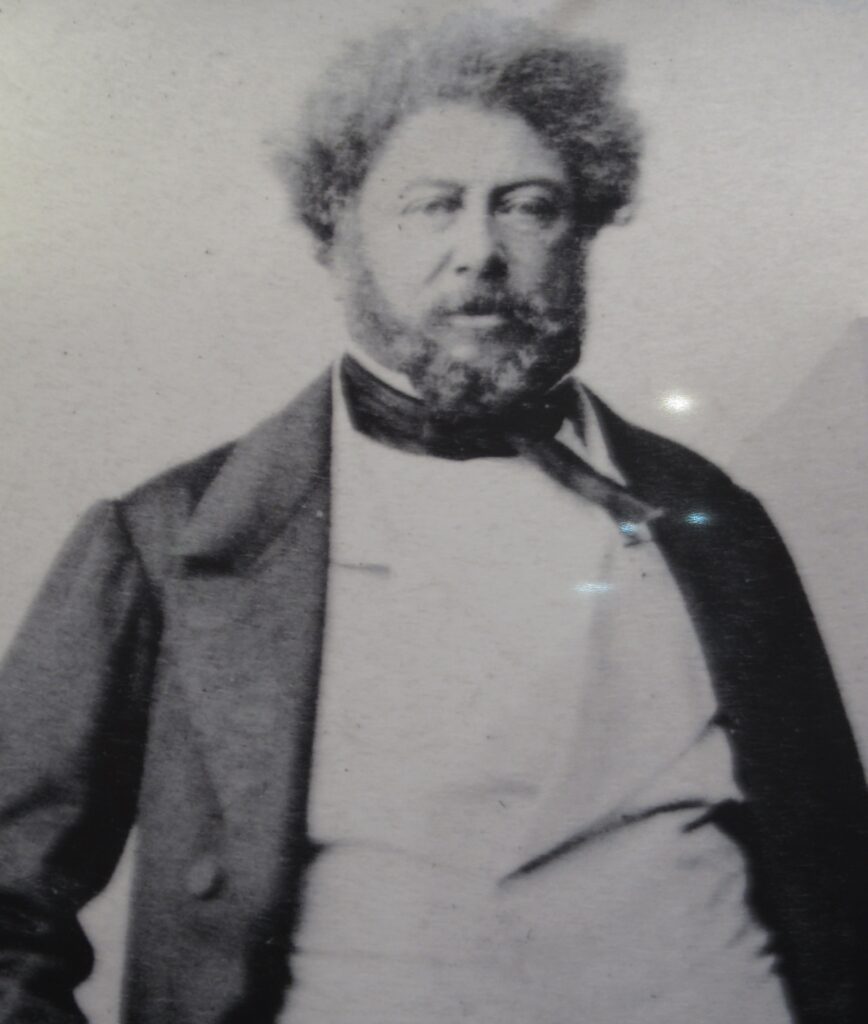

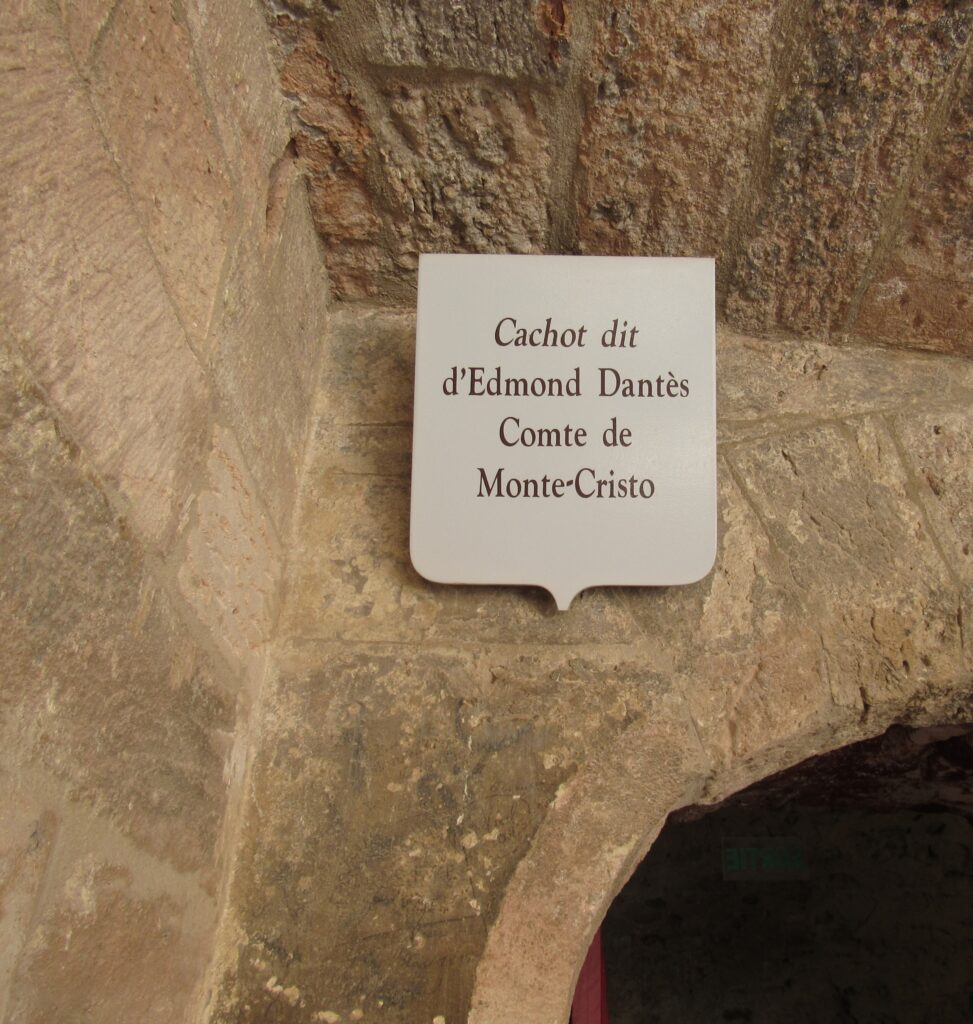

Alexandre Dumas, père, situated The Count of Monte Cristo between 1815 (Napoléon’s escape from Elba) and 1847 (the end of the restoration of the Bourbon regime). This is important because Edmond Dantès was imprisoned for allegedly being a Bonapartiste.

The politics of the story serve as a plot device designed to unjustly imprison the hero, leading the reader to sympathize with his quest for vengeance.

That said, it is helpful to have a bit of historical context with respect to the novel.

“The Literary French Images of Napoléon ”

Jean-Max Guieu, Georgetown University

Like the perception of France and the French in general, the perception of Napoléon in the Anglo-Saxon world is often unflattering. The French being what they are — they even like Jerry Lewis — and Napoléon being a monster, the French are routinely expected to adore without reservation the diminutive megalomaniac who became their Emperor. But, actually, the popular image of Napoléon, as well as the one reflected in literature, is similar in France to the one shared by the rest of the civilized world. For instance, when referring to his life, the French still insist on dissociating Bonaparte, the valiant Jacobin general who inspired Beethoven to write his Eroïca Symphony, from Napoléon, the self-proclaimed Emperor and tyrant who caused the composer to change the dedication “to the memory of a great man”.

However, as with many other historical figures — Alexander the Great, Julius Cesar or Joan of Arc — whose pathetic demise helps them achieve a heroic stature, Napoléon’s memory, long after he had died on an island in the middle of nowhere, has received a certain glamorous post-mortem treatment. As Professor Shahîd stresses, in France — as in the rest of the world — artists saluted the “many facets of Napoléon’s personality: the hero, the romantic, the artist, the conqueror, the superman,” without losing sight of his shortcomings.

Certainly, for the French of today, the Empire still evokes the memory of a glorious past “gone with the wind” but, during a large part of the nineteenth century, the Emperor himself was the incarnation of the hopes of the young men born at the time of the French Revolution. What happened is that, perhaps because Napoléon’s troubled history lasted for less than twenty years, the following generation was able to ignore the reality of the daily life their parents knew under imperial rule. In the end, they would argue, his failure to succeed enhanced the fact that he, at least, had tried; his military victories still outnumbered his defeats and the control he imposed on his people was compensated for by his role as patron of the Arts and of a culture which has had a lasting effect on French society.

As we will see, the representation of Napoléon appearing in the writings of his French contemporaries was ambiguous and reflected their own political perspectives. But in the next generation, it went beyond just showing a need to take up an established canon and make it new: the glow of the golden age of Napoléon, as remembered by the few surviving grognards, became a rich historical background which contrasted strongly to the succeeding tedious political era, even if that recent past was still associated with some unavoidably negative connotations, such as a police state and bloodstained battlefields. Ironically, in Montholon’s Mémoires, Napoléon is described as regretting, in Saint-Helena, not having given Chateaubriand a more important position. The now dignified Chateaubriand, in his posthumous Mémoires d’outre-tombe (published in 1850), devoted a long chapter to Napoléon, in which he drew a famous parallel between him and Washington: the ambitious general organized a coup, became a dictator, and died rejected and forgotten on an island lost in the middle of the ocean, when the ethical one, after he had fought for his republic, returned to normal life like a modern-day Cincinnatus, dying respected by a whole nation.

After Waterloo, Benjamin Constant referred to Napoléon in the Mémoires sur les Cent Jours as “un géant relégué sur un rocher aride et prisonnier de l’étranger” (A giant relegated to an arid rock and imprisoned by foreigners). As expected, when the Bourbons returned to power, the inconstant Constant became a monarchist, albeit a liberal one, since this bon vivant became the supporter of individual rights and religious freedom, under the ultra-Catholic Charles X. With Napoléon ’s fall in 1814, however, (Fouché) could, without too much risk, and with the same sense of timing as with Le Génie du Christianisme, publish his essay De Buonaparte et des Bourbons, describing Napoléon as an “ogre corse” and a “faux grand homme.” In it, he described his vision of the club-footed Talleyrand, walking with the help of Fouché to pledge their new allegiance to Louis XVIII as: “Vice leaning on the arm of Crime.” At the same time, Chateaubriand was hoping they would give him a portfolio: he only got a peerage and the ambassadorship to Sweden, and for a very short while, he was Minister of Foreign Affairs. But when his long-hoped-for Bourbons finally were back in place, Chateaubriand felt bitterly that he had been discarded and soon renounced his political ambitions. With all his romantic pathos, he turned his disappointments into introspection and cast for himself another image altogether.

As one can imagine, the carefully contrived denunciations of Napoléon by contemporary French writers, motivated by political opportunism as they were, did not have much impact. In France, they fell on deaf ears. Yet the fall of Napoléon did not produce the surge in criticism that one would have expected. The return of the Bourbons failed to bring the anticipated renaissance: indeed, it produced both a retreat from some generally well-respected Imperial institutions and a return to the bad old ways of the Ancien Régime. The émigrés had not forgotten anything but they had not learned anything either. Perhaps this explains why the military glory of the Empire soon overshadowed all its bloody defeats, and why the following generation of the 1820’s and 30’s embraced it as an antidote to the pervasive boredom of the monarchist Restoration. For a few years after his demise, any public allusion to Napoléon had been prohibited by the reinstated Bourbons as a sign of conspiracy against their monarchy and therefore only metaphors were used to refer to him (“Him”, “The Man”). After his death, however, the wide publication of the 1823 memoirs by Las Cases (Mémorial de Sainte Hélène) relaunched the more positive myth of Napoléon as the son of the French Revolution.

Contact